12/26/838

First documented storm surge in the North Sea; Approximately 2,500 deaths in what is now the Netherlands.

2/17/1164

First Julian flood: 20,000 dead; First collapse of the Jade Bay, major damage in the Elbe area.

1/16/1219

First Marcellus flood: 36,000 dead: major floods also in the Elbe area; first conveyed eyewitness report.

12/28/1248

Allerkindslein flood: High loss of human life. The historic Elbe island of Gorieswerder is divided into several parts.

12/14/1287

Lucia Flood: Beginning of the formation of the Dollart, 50,000 dead.

11/23/1334

Clemens Flood: Expansion of the Jade Bay.

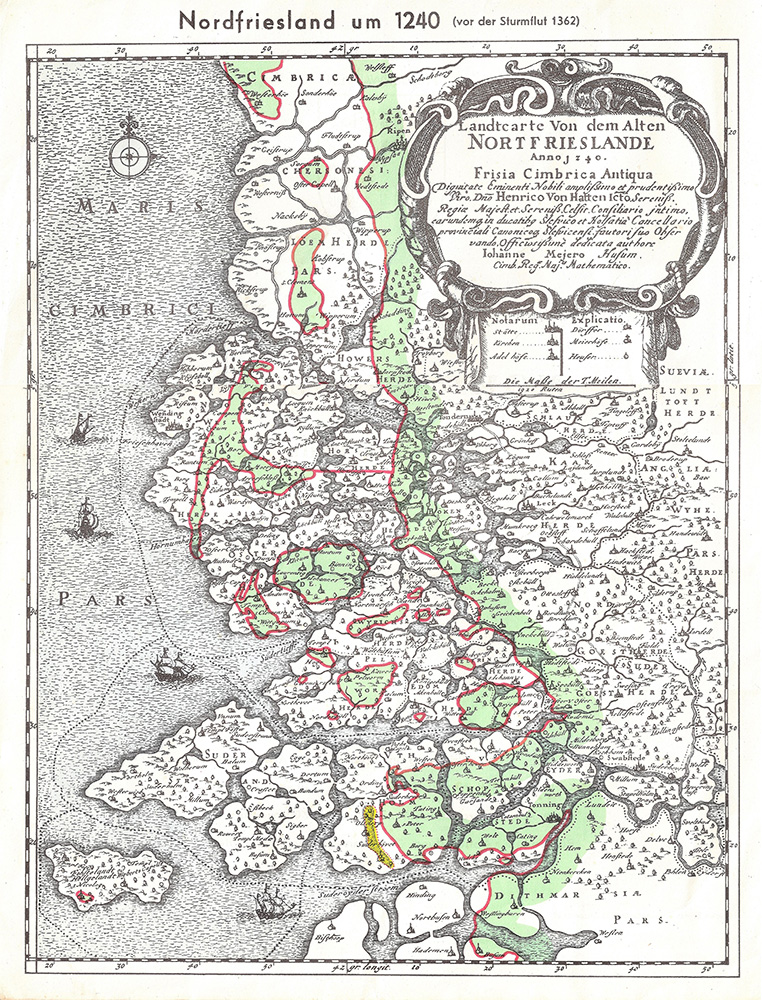

1/16/1362

Second Marcellus Flood, Grote Manndranke: 100,000 dead: first collapse of the Dollart, expansion of Leybucht, Hariebucht, Jade Bay and Eider Estuary, sinking of large parts of North Frisia.

10/09/1374

First Dionyslus flood: Largest extent of the Leybucht up to the city of Norden, sinking of the village of Westeel near Norden.

9/10/1377

Second Dionysiusflut: Dikes near Lütetsburg and Bargebur

torn, the waves hit the walls of the Dominican monastery in Nord.

11/21/1412

Cacilien flood: An entire village at the mouth of the Este was destroyed, and the Elbe island of Hahnöfersand was separated from the mainland.

11/1/1436

Allerhelligen flood: Flooding on the entire North Sea coast, especially in Eiderstedt and Nordstrand.

1/6/1470

Epiphany Flood: Flooding in Eiderstedt, no permanent land losses.

09/26/1509

Cosmas and Damian flood: Breakthrough of the Ems

near Emden, largest expansion of the Dollart, last expansion of the Jade Bay to the northwest.

01/16/1511

Antonius flood, ice flood: breakthrough between Jade and Weser.

10/31 and 11/1/1532

Third All Saints Flood: Several thousand dead in North Frisia, first peak value recorded in the church of Klibüll; Sinking of Osterbur and Ostbense in East Frisia.

11/01/1570

Fourth All Saints Flood: Flooding of the marshes from Flanders to Eiderstedt: large dike breaches in the Altes Land as well as in the Vier- und Marschenlanden; Sinking of the villages of Oldendorf and Westbense near Esens: 9,000 to 10,000 dead between Ems and Weser. High tide mark at the Suurhusen church at NN +4.40 m.

2/26/1625

Carnival flood: An ice flood, dike breaches and major damage in East Frisia and Oldenburg, in the Altes Land and Hamburg, many dikes breaches on Jade and Weser.

10/11/1634

Second Grote Manndranke: Strand Island sinks; What remains are the islands of Nordstrand and Pellworm; at least 8,000 dead.

2/22/1651

Petri flood: “Dane chains” broken on Juist and Langeoog, Dornumersiel was destroyed, there were dike breaches on the mainland.

11/12/1686

Martin’s Flood: Severe damage to dikes from the Netherlands to the Elbe.

12/24 to 12/25/1717

Christmas flood: 11,150 dead from Holland to the Danish coast: the largest storm surge known to date with flooding and devastation of enormous proportions.

12/31/1720 to 01/01/1721

New Year’s flood: higher than Christmas flood; Destruction of the dikes that were poorly repaired after 1717; Sinking of the villages Bettewehr II and Itzendorf

2/3 to 2/4/1825

February flood: 800 dead; There were many dike breaches along the coast and severe loss of dunes on the islands. Highest storm surge on the Elbe until 1962.

1/1 to 1/2/1855

January flood: Heavy destruction on the East Frisian Islands, storm surge mark on Norderney at NN +4.26 m.

3/13/1906

March flood: highest storm surge recorded to date on the East Frisian coast.

1/31 to 2/1/1953

Dutch flood: worst natural disaster of the 20th century in the North Sea area. In the Netherlands approx. 1,800 dead, England and Belgium more than 2,000 dead; Total damage more than €500 million: no major damage to the German coast, but an impetus to check the dikes.

2/16 to 2/17/1962

February storm surge, Second Julian flood: 340 dead, 19 of them in Lower Saxony, approx. 28,000 apartments or houses damaged and 1,300 completely destroyed; highest storm surge to date East of the Jade with 61 dike breaches in Lower Saxony; The Elbe area and its tributaries were particularly affected.

1/3/1976

January flood: highest storm surge to date on almost all pegs on the German North Sea coast: numerous dike breaches in Kehdingen and the Haseldorfer Marsch.

11/24/1981

November flood: Highest peak water level in North Frisia with NN +4.72 m at the Dagebüll gauge.

1/28/1994

January flood: Highest peak water levels on the Ems with NN +4.75 m at the Weener gauge and on the Wese with NN +5.33 m at the Vegesack gauge.

12/3/1999

Anatol: short-term increase with very high water levels in the entire North Sea region; The storm subsided before the astronomical flood occurred in Cuxhaven, otherwise the values of 1976 had been exceeded in the Elbe area.

11/01/2006

Fifth All Saints Flood: Very severe storm surge with water levels exceeding the 1994 levels in the Ems area, dike collapses on the East Frisian islands of Juist, Langeoog and Wangerooge…

This list was assembled by Christian von Wissel of Bremer Zentrum für Baukultur. It was part of the exhibition “Deichstadt #1” in spring 2024.