In his beautifully written account of the 2011 tsunami in Tohoku, northern Japan, and it’s aftermath, Richard L. Parry also describes the role of the cult of ancestory in grievance for those who died in the tsunami. Vacant home addresses for example play a recurring role in how people were dealing with grief and loss. Perry’s account gives an example of societies using old customs and believe systems in sometimes unexpected ways to help them deal with current loss.

The following excpert is from pages 99 – 102 of the 2017 edition of “Ghosts of the Tsunami” by R.L. Parry:

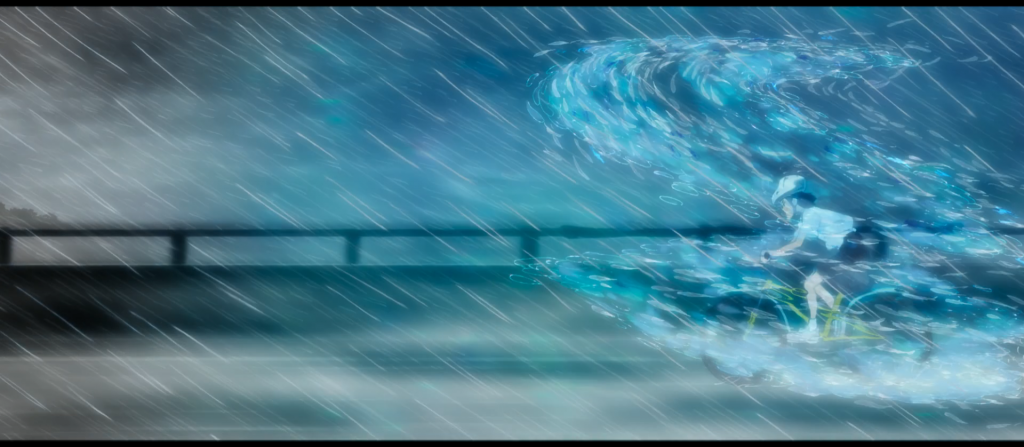

“Haltingly, apologetically, then with increasing fluency, the survivors spoke of the terror of the wave, the pain of bereavement and their fears for the future. They also talked about encounters with the supernatural.

They described sightings of ghostly strangers, friends and neighbours, and dead loved ones. They reported hauntings at home, at work, in offices and public places, on the beaches and in the ruined towns. The experiences ranged from eerie dreams and feelings of vague unease to cases of outright possession.

A young man complained of pressure on his chest at night, as if some creature was straddling him as he slept. A teenage girl spoke of a fearful figure who squatted in her house. A middle-aged man hated to go out in the rain, because of the eyes of the dead, which stared out at him from puddles.

A civil servant in Soma visited a devastated stretch of coast and saw a solitary woman in a scarlet dress far from the nearest road or house, with no means of transport in sight. When he looked for her again, she had disappeared.

A fire station in Tagajo received calls to places where all the houses had been destroyed by the tsunami. The crews went out to the ruins anyway, prayed for the spirits of those who had died— and the ghostly calls ceased.

A taxi in the city of Sendai picked up a sad-faced man who asked to be taken to an address that no long existed. Halfway through the journey, the driver looked into his mirror to see that the rear seat was empty. He drove on anyway, stopped in front of the levelled foundations of a destroyed house and politely opened the door to allow the invisible passenger out at his former home.

At a refugee community in Onagawa, an old neighbour would appear in the living rooms of the temporary houses and sit down for a cup of tea with their startled occupants. No one had the heart to tell her that she was dead; the cushion on which she had sat was wet with seawater.

Such stories came from all over the devastated area. Priests — Christian and Shinto, as well as Buddhist – found themselves called on repeatedly to quell unhappy spirits. A Buddhist monk wrote an article in a learned journal about ‘the ghost problem’, and academics at Tohoku University began to catalogue the stories. In Kyoto, the matter was debated at a scholarly symposium.

“Religious people all argue about whether these are really the spirits of the dead,’ [priest] Kaneta told me. ‘I don’t get into it, because what matters is that people are seeing them, and in these circumstances, after this disaster, it is perfectly natural. So many died, and all at once. At home, at work, at school – the wave came in and they were gone. The dead had no time to prepare themselves. The people left behind had no time to say goodbye. Those who lost their families, and those who died – they have strong feelings of attachment. The dead are attached to the living, and those who have lost them are attached to the dead. It’s inevitable that there are ghosts.’

He said: ‘So many people are having these experiences. It’s impossible to identify who and where they all are. But there are countless such people, and their number is going to increase. And all we do is treat the symptoms.’

When opinion polls put the question ‘How religious are you?’, Japanese rank among the most ungodly people in the world. It took a catastrophe for me to understand how misleading this selfassessment is. It is true that the organised religions, Buddhism and Shinto, have little influence on private or national life, But over the centuries both have been pressed into the service of the true faith of Japan: the cult of the ancestors.

I knew about the household altars, or butsudan, which are still seen in most homes and on which the memorial tablets of dead ancestors — the ihai — are displayed. The butsudan are cabinets of lacquer and gilt, with openwork carvings of flowers and trees; the ihai are upright tablets of black lacquered wood, vertically inscribed in gold. Offerings of flowers, incense, food, fruit and drinks are placed before them; at the summer Festival of the Dead, families light lanterns to welcome home the ancestral spirits. I had taken these picturesque practices to be matters of symbolism and custom, attended to in the same way that people in the West will participate in a Christian funeral without any literal belief in the words of the service. But in Japan spiritual beliefs are regarded less as expressions of faith than as simple common sense, so lightly and casually worn that it is easy to miss them altogether. ‘The dead are not as dead there as they are in our own society,’ wrote the religious scholar Herman Ooms. “It has always made perfect sense in Japan as far back as history goes to treat the dead as more alive than we do… even to the extent that death becomes a variant, not a negation of life.’

At the heart of ancestor worship is a contract. The food, drink, prayers and rituals offered by their descendants gratify the dead, who in turn bestow good fortune on the living. Families vary in how seriously they take these ceremonies, but even for the unobservant, the dead play a continuing part in domestic life. For much of the time, their status is something like that of beloved, deaf and slightly batty old folk who cannot expect to be at the centre of the family, but who are made to feel included on important occasions. Young people who have passed important entrance examinations, got a job or made a good marriage kneel before the butsudan to report their success. Victory or defeat in an important legal case, for example, is shared with the ancestors in the same way.

When grief is raw, the presence of the deceased is overwhelming. In households that had lost children in the tsunami, it became routine, after half an hour of tea and chat, to be asked if I would like to ‘meet’ the dead sons and daughters. I would be led to a shrine covered with framed photographs, with toys, favourite drinks and snacks, letters, drawings and school exercise books.

One mother commissioned carefully photoshopped portraits of her children, showing them as they would have been had they lived – a boy who died in primary school smiling proudly in high-school uniform, an eighteen-year-old girl as she should have looked in kimono at her coming-of-age ceremony. Another decked the altar with make-up and acrylic fingernails that her daughter would have worn if she had lived to become a teenager. Here, every morning, they began the day by talking to their dead children, weeping love and apology, as unselfconsciously as if they were speaking over a long-distance telephone line.”