The Man from Atlantis was a TV series that cashed in on the popularity of underwater films in the 1960s and 1970s. Even though the series didn’t run for long, it was impressive enough to birth multiple adaptations as comic books and novels. From today’s perspective the whole project seems a bit silly with questionable character drawing and superficial visual attractions. I was however impressed by the great emphasis on scientific details in the story lines. The episodes are also a bit like disguised lessons in popular ocean science.

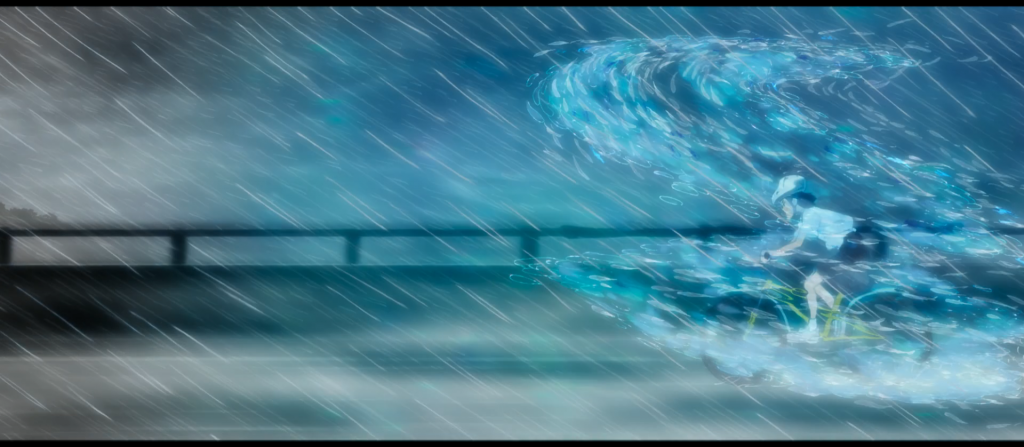

The episode “Melt Down” written by Tom Greene deals with a sudden global sea level rise caused by melting of the polar ice, intentionally induced by the series’ super-villain Mister Schubert. You could call it prophetic, but then of course, the reason for the meltdown here is not collective political failure but individual roguery. The depiction of the effects of sea level rise are spooky nevertheless. Looking at it today, 50 years later, this little dialog seems to recapitulate perfectly the absurdity of the current situation along the coasts of the USA. “Hey, aren’t you from that Ocean Institute? You know what’s causing all of this?”

It’s quite funny – if only it wasn’t quite as sad…

Thanks to my comic dealer at the fantastic Fantastic Store for the lead!