In a beautiful article from 2019, Patrick Nunn gives a couple of examples for protection architecture that serve both material and spiritual purposes. I would argue, that this is the case for any protection structure also today, at least if it is visible. The interesting question here is not, whether a spiritual barrier was or is working today, but rather what functions it fulfills for the well being of the community and thus its protection in a broader sense.

Here are some excerpts with examples from Brittany (France), Serbia and the UK:

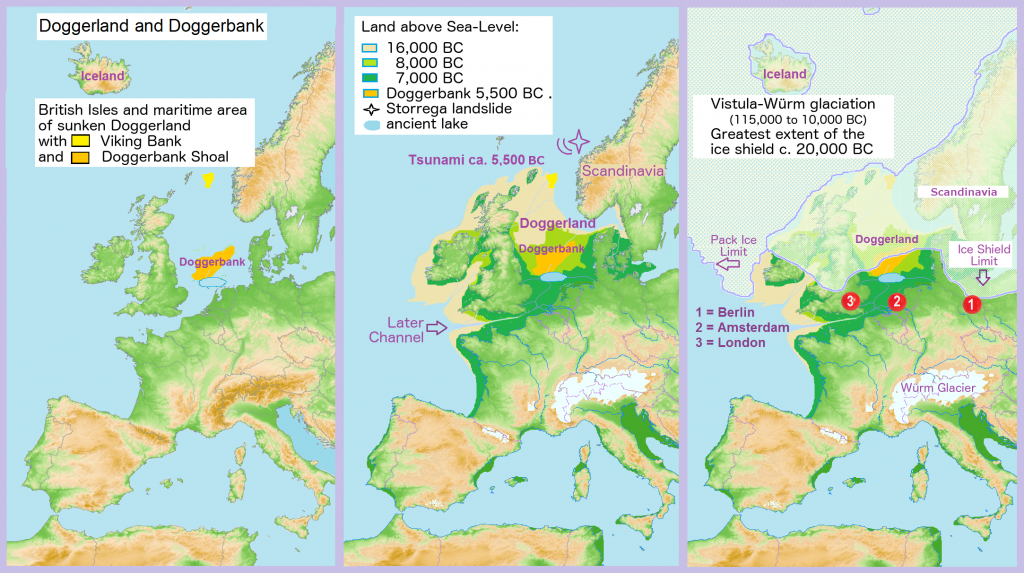

“Take the stone lines at Carnac, in Brittany, some of which extend for kilometres and involve thousands ofmenhirs, once regarded as boundary markers or memorials to fallen warriors. The idea of Serge Cassen that these stone lines represent “a cognitive barrier” between the physical and metaphysical worlds intended to halt the disastrous impacts of rising sea level in the Gulf of Morbihan more than 6.000 years ago is in keeping with what we are learning elsewhere.

“Neatly arranged deposits of once-valuable objects such as stone tools, even human remains, may have been intentionally created as votive offerings to divinities to stop the ocean’s rise. Cemeteries may have been intentionally situated on coasts, symbolically stabilising them in the minds of local peoples. Sandstone sculptures of fish gods from Lepenski Vir inSerbia may have been totems intended to prevent inundation.”

“Even physical barriers, long recognised as useless against the encroaching ocean, may have become symbolic; an example of wooden structures from Flag Fen near Peterborough in the UK was interpreted in this way by Francis Pryor.”