In 1783 an unsual seismic event sequence occured along the Strait of Messina between the island Sicily and mainland Italy. Katrin Kleemann from LMU Munich writes: “Between 5. February and 28. March 1783, five strong earthquakes shook Calabria and Sicily and were followed by hundreds of aftershocks in the following years. The earthquakes caused ten tsunamis.”

That same year additional earthquakes were reported from western France and Geneva on July 6., in Maastricht and Aachen on August 8., and in northern France on December 9. This was not too long after the disastrous earthquake and tsunami that hit Lisbon in 1755.

All these events were widely communicated and written about all across Europe. It was the age of enlightment and the disasters challenged religious, philosophical and political views of the time but also sparked artistic creativity.

Societies were in high demand for images of the disasters and artists, who naturally could not work from first hand observation and experience, were forced to invent formal solutions for this problem.

One strategy was to combine different temporal levels in one painting: the moment before the event, the aftermath, and sometimes even events that had no logical connection other than in the public mind.

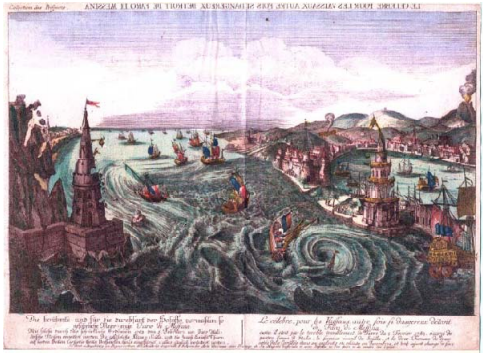

Katrin Kleemann writes about this image: “This hand-colored copper engraving portrays the Strait of Messina from the north at the moment the earthquake struck. To the left it depicts the coast of Calabria, to the right the harbor of Messina, and to the far right an erupting Mount Etna, although it did not actually erupt in 1783”, but in 1780 and then again in 1787.

Another striking example is the painting »Vue

de la Palazzata de Messine au moment du tremblement

de terre« by French artist Jean Houel.

Hans-Rudolf Meier writes: “Jean Houel published in his »Voyage pittoresque« one year after the earthquake in the Sicilian port. Houel, who had traveled in Sicily before the earthquake and had not himself seen the extent of the destruction—to say nothing of the event itself—successfully recorded before and after in one picture by depicting the palace in the margins as a ruin, but showing it still intact in the middle of the picture. Here the special quality of buildings for impressive representations of the effect of a disaster becomes evident: on a building the sudden transformation from a consummate cultural achievement to a ruin can be perceived as a symbol of transience. In Houel’s engraving the observer, similar to today’s television viewer, witnesses the moment of destruction from a secure distance. The churning sea in the foreground cannot bridge this distance either, but

it is intended to suggest something of the danger—and

thus the authenticity—to which the fictive recorder of

the scene might have been exposing himself.

From:

Katrin Kleemann, Living in the Time of a Subsurface Revolution: The 1783 Calabrian Earthquake Sequence (2019)

Hans-Rudolf Meier, The Cultural Heritage of the Natural Disaster: Learning Processes and Projections from the Deluge to the »Live« Disaster on TV (2007)