Date and title of this wood print are unfortunately unknown to me. This is the source.

Date and title of this wood print are unfortunately unknown to me. This is the source.

It’s a rather popular architectural motif, particularly of course in coastal and riverside cities. I wonder if there ever has been a historical study of the wave in architecture. Here are a few random examples from Europe:

Dessauerstraße, Hemshof Ludwigshafen, Germany. I couldn’t find out about the architect nor he date of these buildings.

Built over the course of more than a decade and finished in 2018: The Wave in Vejle, Denemark, designed by Henning Larsen.

Elbphilarmonie in Hamburg, Germany. Opened in 2016, by architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron.

Inside of Multihalle, in Mannheim, Germany, built by Frei Otto in 1975.

In June 2023 massive wildfires in Canada caused air pollution in New York to a scale not known to New Yorkers. Besides the serious health issues the smoke-filled air causes, it also tinted the whole city in a curious sepia like color. The remarkable images, the New Yorker chose to accompany this article, show that the editors clearly recognized the aesthetic qualities. For a day or more all contemporary images of New York appeared like paintings from the romantic period of the 19. Century. All photographs are by Clark Hodgin for The New Yorker.

“Tides” (alternative title “The Colony”) is a sci-fi movie from 2021 about a post-apocalyptic world at the moment the first human communities are about to re-settle again. The only territory suitable is a coastal strip that is covered by tides twice a day. The area is a tidal zone, not quite land and not quite sea, with little to no vegetation and natural shelter for the people to build a more permanent habitat.

The landscape and weather in the story are the same as on the location, the movie was filmed. “Tides” was largely filmed outdoors on the small island Neuwerk in the German Tidelands, situated between the estuaries of the rivers Weser and Elbe.

Director Tim Fehlbaum explained in an interview how this landscape inspired the movie plot in the first place:

“For the outdoor scenes we went to the German Tidelands, which was where the idea for the film started. I’m a very visual director and my ideas often have a visual trigger. I had never been to the Tidelands and having grown up in the Swiss mountains being at the low point of Germany was eye-opening. Looking out at this expanse of water was so interesting because in an hour or so, everything you just saw becomes covered in water. The floods in the film are real, and they come in twice a day. Shooting there was exceedingly difficult because we could never shoot much longer than two or three hours, and I always wanted to keep shooting, but it becomes a question of minutes before the water is at your knees and suddenly up to your chest.”

You could say, the movie is really an exploration of this landscape and the living conditions and the atmosphere in tidal zones. That human renewal after the partial retreat and ecological meltdown takes place in such a tidal zone is interesting as it references this landscape as a realm of opportunity, transition and change – a liminal space full of potential rather than decay.

I find this inspirational in regard to our current situation of ecological and social transformation. Author Kim Stanley Robbinson made a similar reference to the “intertidal” as a space of opportunity and renewal when sketching his “Super Venice” in the post-apocalyptic novel “New York 2140” four years earlier. It is striking how both works are set in tidal zones, how both interpret them as spaces of renewal, and yet how radically different they paint this landscape. You can read my post on Robbinson’s book here.

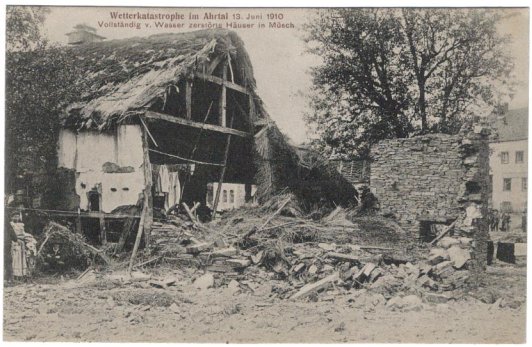

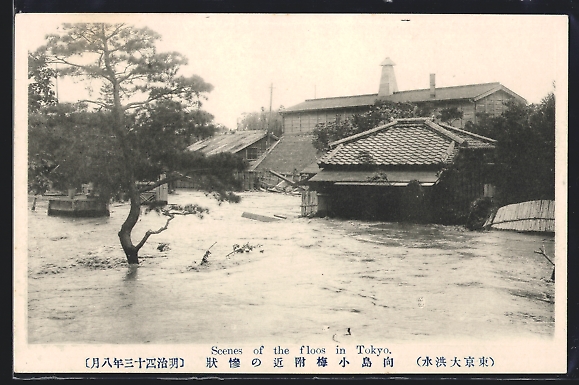

In Germany as well as in many other countries, images of extreme floods often found their way on postcards. Here is a selection of postcards. (click on the image to find the online source)

1909

1910

1914

1920

1920

1929

2002

undated postcard from Tokyo, Japan

undated postcard from Panama, probably 1924

There are only a limited number of options to deal with SLR and land subsidence. One of the more obvious ones is raising buildings. There is of course limitations as to how many buildings you can possibly raise to save the habitats from inundation. Raising a whole city? Not likely.

Yet in the middle of the 19. Century the city of Chicago on the shore of Lake Michigan tried just that. The story is so extraordinary that I first assumed it to be an urban folklore from a place that has no shortage of urban legends. By the 1850s, the sanitary and health situation in Chicago had become unacceptable due to large pools of standing and infested water building in the city. Central Chicago is almost at sea level of Lake Michigan, making drainage difficult. In order to install a new sewerage system, the street level of central Chicago as well as most of the buildings had to be elevated between 1 and 2 meters.

The feat was achieved in a piecemeal fashion and over the cause of several years. Many large buildings like the Tremont House hotel (6 stories high and over 1 acre (4,000 m2) of ground space) or the Robbins Building were elevated in one piece by use of jackscrews:

“Business as usual was maintained as this large hotel ascended, and some of the guests staying there at the time—among whose number were several VIPs and a US Senator—were oblivious to the process as five hundred men worked under covered trenches operating their five thousand jackscrews. One patron was puzzled to note that the front steps leading from the street into the hotel were becoming steeper every day and that when he checked out, the windows were several feet above his head, whereas before they had been at eye level. This hotel building, which until just the previous year had been the tallest building in Chicago, was raised 6 feet (1.8 m) without incident.” (from wikipedia)

The Franklin Building was elevated in 1860 not with jackscrews but with hydraulic power. In the local newspapers on April 30th, 1860, citizens were invited to witness the event with the following note on the front page:

“The public are respectfully invited to be present between the hours of 1 and 3 o’clock P. M. on Monday, to witness the process of raising buildings by Hydraulic Pressure, at the four story brick buildings known as the Franklin House, now being raised to grade, and at that hour the machinery will be in operation.”

The images and articles from this period of the city’s history have become emblematic of the spirit of Chicagoans and their entrepreneurial bravery and wit. The Chicago Tribune in 1865 called it a “truly Herculean task”. In a sense, Chicago was really pulling herself up by her boot strings. The story serves as a striking example of how adaptation measures constitute to urban history and identity.

Thanks to Jeff Goodell’s video lecture for the lead.

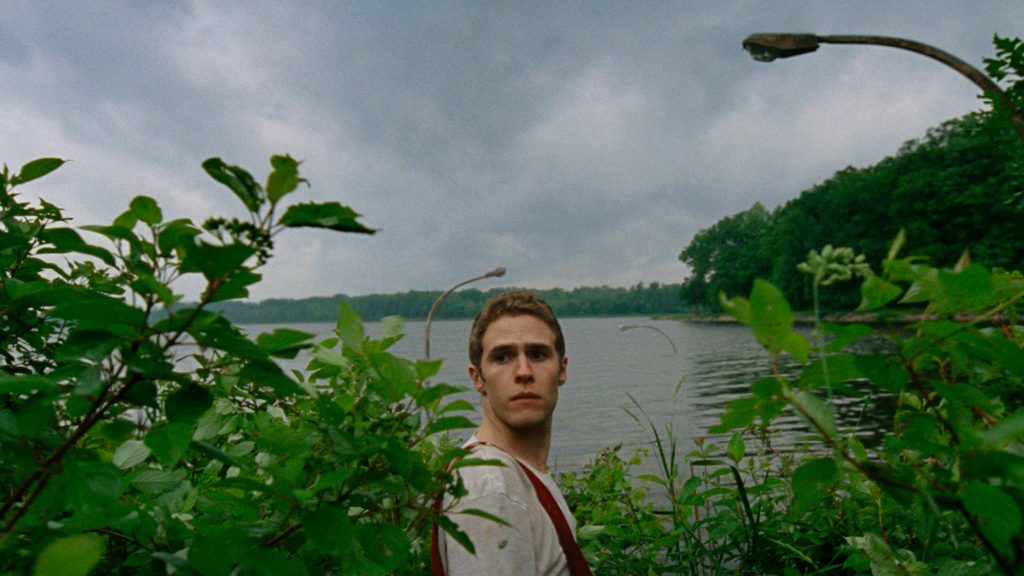

Ryan Goslings 2014 movie “Lost River” is most of all a portrait of urban decay and our fascination with decay in a broader sense. The film juxtaposes the stylized display of bodily mutilation and destruction in a Grand Guignol style cabaret on the one side and the at once slow and dramatic decay of urban environments in the US rust belt on the other.

While buildings on fire – an image particularly indicative of the Detroit situation in the 1980s and 1990s – or urban structures overgrown by vegetation are the two main visual ciphers for urban decay in the movie, a flooded town also plays a central role.

As one protagonist explains, the town is called Lost River, because a section of it was once purposefully submerged when a water reservoir was built. Beneath the river lie the remains of that city and also a prehistoric theme park. Pre-historic monsters are said to live in the deep water. The idea of a prehistoric past lurking underneath the water’s surface is reminiscent of J.G Ballard’s 1962 novel “Drowned World“, where global climate change and flooding causes nature to regress into an early state of evolution.

The movie pays little attention to this submerged town. Instead it effectively uses one rather simple image in several scenes: the street lights that stick out of the water and create an eerie sense of displacement and confusing proportions.

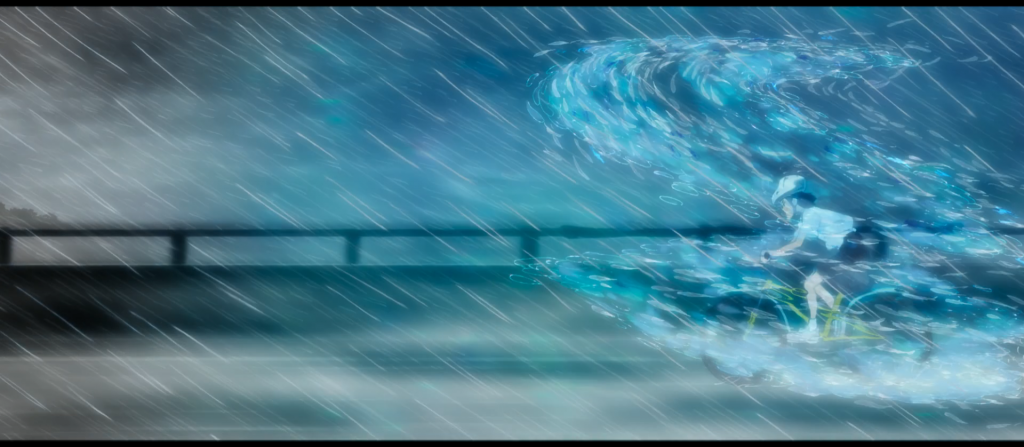

2019 Japanese anime movie “Children of the Sea” (original title: 海獣の子供, which translates roughly as “Children of Sea Monsters”) is set in a fictitious island in the Okinawa region of Japan. The movie directed by Ayumu Watanabe puts a lot of effort into creating the image of a culture and a way of life, that is aquatic or located in a fluid continuum between dry land and water, the city and the sea. Here are screen shots from two scenes of intense tropical rainstorm that blur the distinction between land and sea.

Another noteworthy scene is the following, set on a pier that is aligned with concrete tetrapopds. These tetrapods have been used since the 1950s all over the world to protect coasts against erosion and flooding. They are particularly prominent across Okinawa and have come to define the look of the coasts there. (See the wiki article here)

Since the movie’s plot is about the meeting and friendship between two brothers born in the sea and a city girl and the girl’s eventual emergence into the underwater world, the tripods here seem to symbolize the community’s effort to maintain the separation between land and sea and protect it’s people from the forces bur also the allure of the ocean.

Jan Asselijn (1610–1652): “Breach of St. Anthonis-Dike near Amsterdam”, 1651.

“During the night of 4-5 March 1651 the Saint Anthony’s Dike was breached near Amsterdam. Jan Asselijn portrayed the fiercely flowing water with a strong sense of drama. The billowing cloak of the man at the left shows that the storm is not yet over, however the squalls are already moving on at the right. The vivid red contrasts sharply with the bright blue of the parting clouds.”

(from the website of Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, NL)