The 19. Century was not only the century of industrialization, the spark that “set human civilization aflame” (Andri Snaer Magnason). Between 1800 and 1815 half a dozen large volcanic eruptions all across the globe significantly changed the climate in China as well as all across Europe and practically all continents. What followed was “the year without a summer” 1816 which did not only bring massive crop failures as well as floods and resulting famines and other hardships to societies worldwide, it also influenced European culture so profoundly that a whole new era of the arts and philosophy developed that had a lasting impact on all of modern society: Romanticism. 1816 is not such a distant past and the paintings, poems, novels and scientific treaties of that era by Caspar David Friedrich, Lord Byron or Mary Shelley remain central to our cultural canon and identity today. In fact, all these climate change stories and images have been right in front of our eyes, in museums, libraries, on t-shirts and advertisements all along. To understand better what’s ahead of us now, we should seek advise from ourselves just seven generations back.

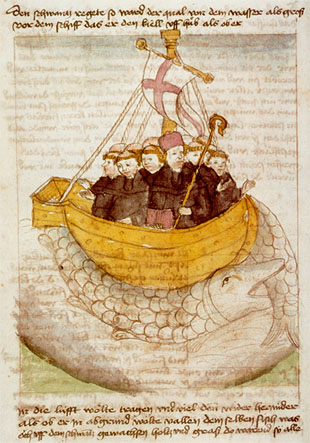

This is an image of the first page of Lod Byron’s famous poem “Darkness” from summer 1816. The full text of the poem and more information about the impacts of “The Year without a Summer” can be found online.