In a very nice, comprehensive and extensive article, Dutch author Thijs Weststeijn, describes the role of culture in forming a climate conscience. The article not only describes the threats to cultural heritage the world over, particularly flooding, and the efforts to save it, but he also makes a case for using cultural heritage to create awareness and ultimately climate action. Here are two short quotes:

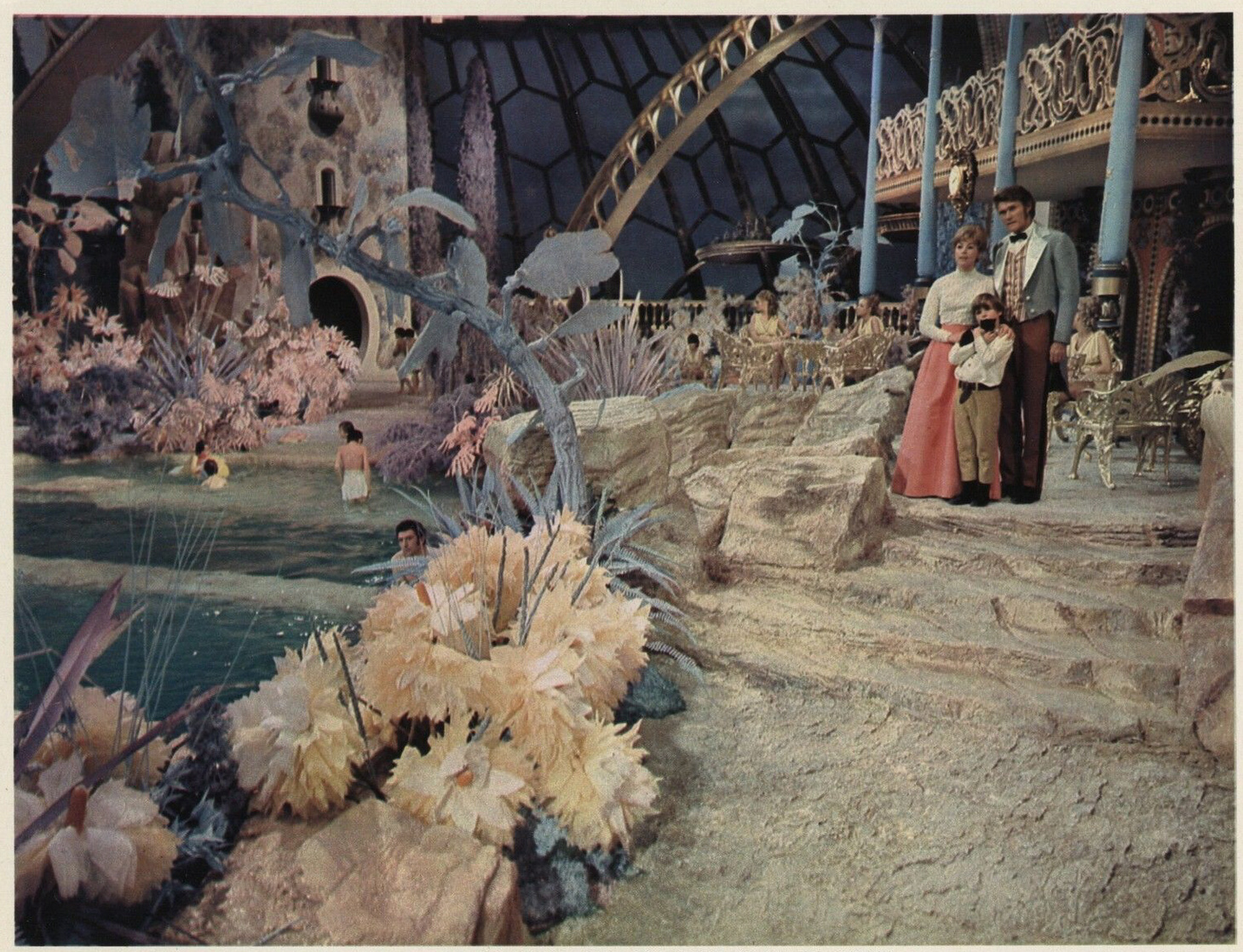

“Perhaps an awareness that the building blocks of one’s own civilisation are under threat might mobilise new groups, for whom the disappearing of coral reefs, say, remains too abstract or remote. Behavioural scientists point out that, when confronted with overwhelming amounts of scientific data, such as that continuously produced by climatologists, people actually become less likely to take action (see Kari Norgaard’s book Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life, 2011). Instead, people have to be affected on a deep emotional, psychological and spiritual level, which suggests that the layered sensations we experience in encounters with heritage – historical connection, aesthetic appreciation, and solastalgia – might motivate people in new ways.”

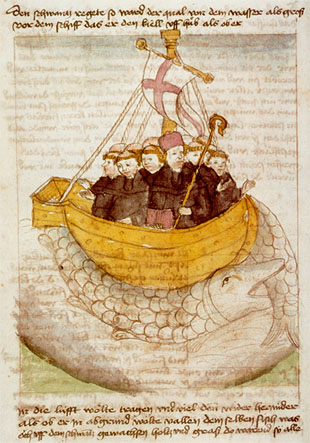

“A focus on cultural heritage also offers new perspectives on human agency in the face of the climate crisis. This heritage has, after all, been made by humans and so by human hands we should be able to save it. Besides, historic heritage, while transcending the lifespan of one or more human generations, is less intractable to us than the ‘deep time’ associated with the evolution and extinction of coral reefs and other endangered creatures.”

Weststeijn also sketches future scenarios for cities and cultural sites in the following excerpt:

“One can imagine the partially flooded centres of Venice, Hoi An or Miami becoming particularly attractive tourist destinations for the duration of their disappearing (in a state of ‘dark euphoria’ described by the futurist Bruce Sterling in 2009), before turning into a diver’s paradise. And perhaps from the perspective of ‘deep time’ the man-made polder landscape was never a feasible project to begin with, and Dutch hydrologists might eventually, with a sigh of relief, surrender their lands back to the sea. Such visions are not necessarily long-term scenarios since, now, even the possibility of handing our heritage to the next generation appears impossible.”