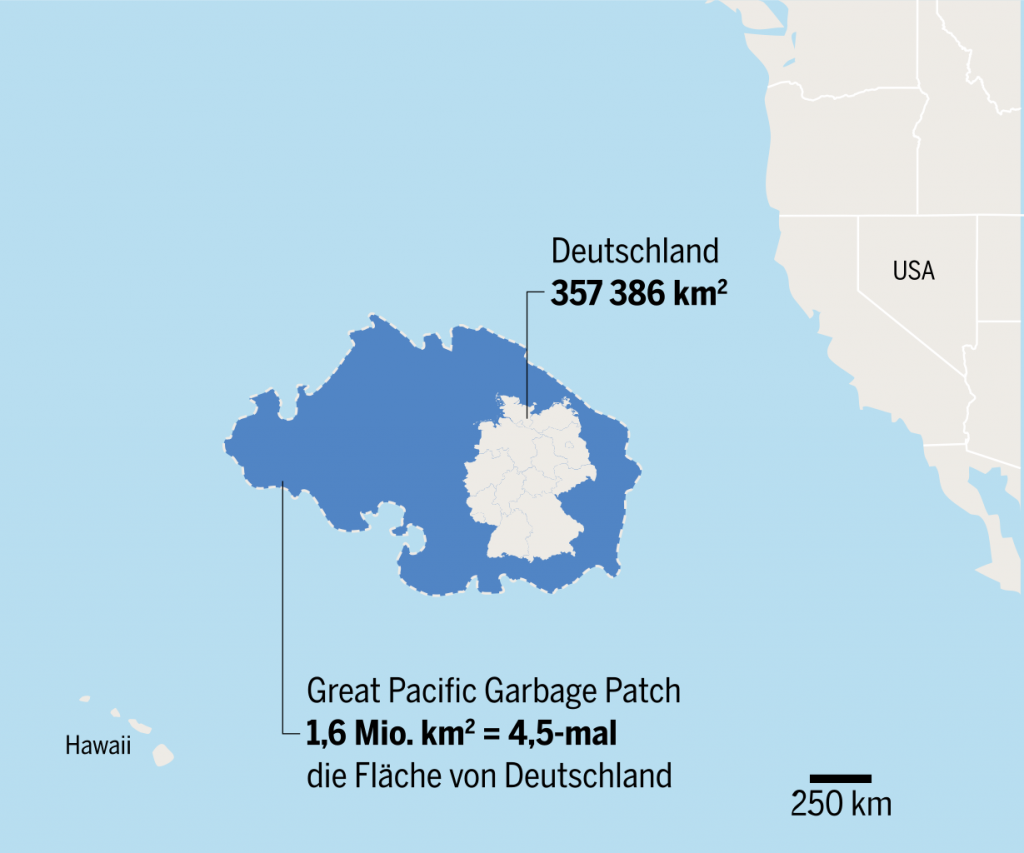

When I read about this assembly of plastic garbage, I was inevitably reminded of stories out of the saga “Erik the Red” or the Irish Legend of Saint Brendan. In other words, it has everything for being a modern myth, a contemporary fairy tale: A gigantic new island that appeared in the pacific ocean suddenly. It’s size is questionable. It is floating, so it’s exact position is also questionable. It is very hard to get to and it is dangerous.

Take for example this excerpt from National Geographic:

“Many expeditions have traveled through the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Charles Moore, who discovered the patch in 1997, continues to raise awareness through his own environmental organization, the Algalita Marine Research Foundation. During a 2014 expedition, Moore and his team used aerial drones, to assess from above the extent of the trash below. The drones determined that there is 100 times more plastic by weight than previously measured. The team also discovered more permanent plastic features, or islands, some over 15 meters (50 feet) in length.”

And a nameless Captain is quoted: “Fishermen shun it because its waters lack the nutrients to support an abundant catch. Sailors dodge it because it lacks the wind to propel their sailboats.”

So while islands like Tuvalu and cities like Jakarta are projected to sink beneath the sea in the next 100 years to join Atlantis and the many, many sunken islands and cities of our mythology, new and fascinating islands appear.

I wonder if the Great Pacific Plastic Patch too will become the stuff of songs and poetry in 200 years from now.