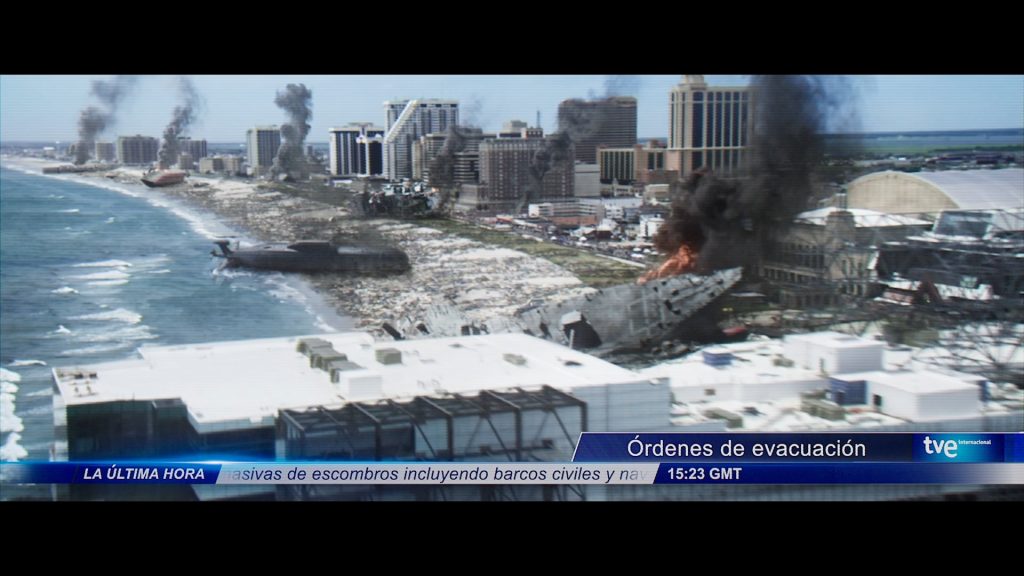

What happens to cities when they become half or seasonally flooded? Kim Stanley Robinson draws a picture of an intertidal New York of the future, where New Yorkers still live in high rises and move across the city on boats and bridges. But there is also a jurisdical aspect to the intertidal zone. Here is one of many sections of his book New York 2140 that discuss the politics and philosophy of living in an intertidal zone:

That said, the intertidal zone was turning out to be harder to deal with than the completely submerged zone, counterintuitive though that might seem to people from Denver, who might presume that the deeper you are drowned the deader you are. Not so. The intertidal, being neither fish nor fowl, alternating twice a day from wet to dry, created health and safety problems that were very often disastrous, even lethal. Worse yet, there were legal issues.

Well-established law, going back to Roman law, to the Justinian Code in fact, turned out to be weirdly clear on the status of the intertidal. It’s crazy to read, like Roman futurology:

The things which are naturally everybody’s are: air, flowing water, the sea, and the sea-shore. So nobody can be stopped from going on to the sea-shore. The sea-shore extends as far as the highest winter tide. The law of all peoples gives the public a right to use the sea-shore, and the sea itself. Anyone is free to put up a hut there to shelter himself. The right view is that ownership of these shores is vested in no one at all. Their legal position is the same as that of the sea and the land or sand under the sea.

Most of Europe and the Americas still followed Roman law in this regard, and some early decisions in the wake of the First Pulse had ruled that the new intertidal zone was now public land. And by public they meant not government land exactly, but land belonging to “the unorganized public,” whatever that meant. As if the public is ever organized, but whatever, redundant or not, the intertidal was ruled to be owned (or un-owned) by the unorganized public. Lawyers immediately set to arguing about that, charging by the hour of course, and this vestige of Roman law in the modern world had ever since been mangling the affairs of everyone interested in working in—by which I mean investing in—the intertidal. Who owns it? No one! Or everyone! It was neither private property nor government property, and therefore, some legal theorists ventured, it was perhaps some kind of return of the commons. About which Roman law also had a lot to say, adding greatly to the hourly burden of legal opinionizing. But ultimately the commons was historically a matter of common law, as seemed appropriate, meaning mainly practice and habit, and that made it very ambiguous legally, so that the analogy of the intertidal to a commons was of little help to anyone interested in clarity, in particular financial clarity.

You can read the full book here.