This impressive photo of the Vietnamese metropolis in the Mekong Delta was taken by Lizzie Yarina, a researcher from the MIT Urban Crisis Lab and it accompanies her insightful article “You’re sea wall won’t save you”.

This impressive photo of the Vietnamese metropolis in the Mekong Delta was taken by Lizzie Yarina, a researcher from the MIT Urban Crisis Lab and it accompanies her insightful article “You’re sea wall won’t save you”.

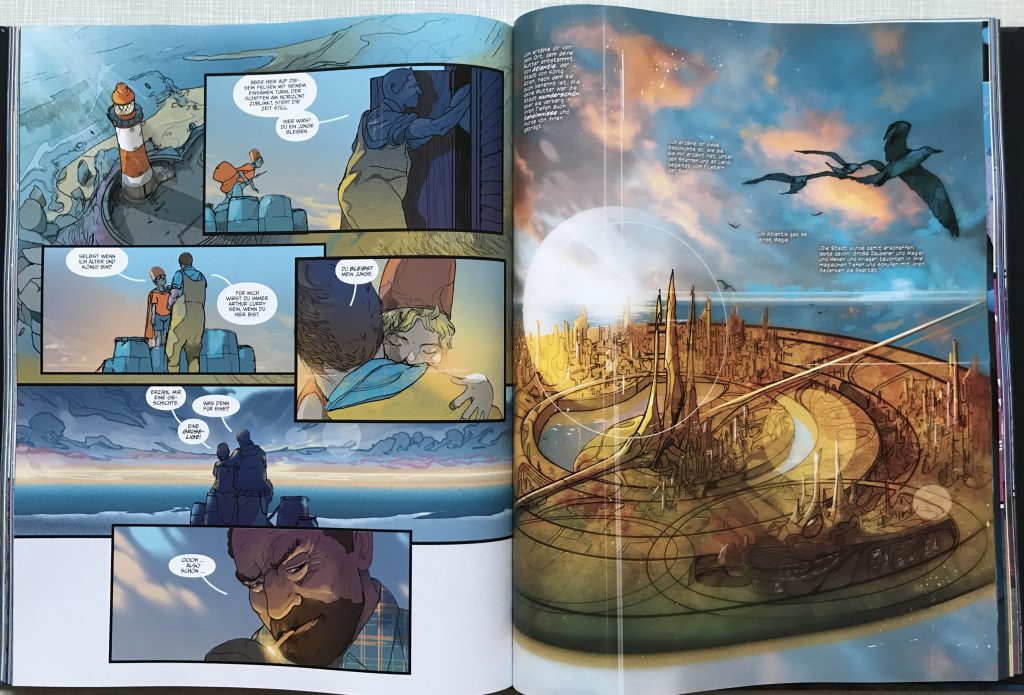

Last year author Ram V and artist Christian Ward published a new three piece comic book on the DC-superhero Aquaman. (I have commented on the Aquaman movie from the same year here and here.) The story is not really about Atlantis, acording to the DC universe the sunken kingdom of Aquaman’s mother. But in it Aquaman tells the story of the kingdom, as he says it was told to him by his father once. What makes this, one of countless variations of the myth, interesting to us today, is the role that the (suppressed) fear of submergence plays in it.

According to the tale, Atlantis was a swimmin city and the Atlantan people were blessed with a magic that helped them create their city and become powerful. This secret power could be accessed by magicians and kings but the power also accessed and read the minds of these rulers and eventually threatened to manifest their suppressed fears as well as their desires. “And which was the one fear that haunted every man, every woman and every child in Atlantis every day,” the text reads. “What if Atlantis were to drown?” (my translations from the German print version)

And of course this is what happens: Atlantis sinks beneath the sea level. It’s rulers manage to create an underwater habitat and thereby safe the population while also sending the magic power source, called “Dark World”, away into outer-space. The text concludes: “The mystery in Atlantis’ heart was both its creative force and its downfall.”

While the fall of Atlantis is usually used as a moral metaphor for blind greed and hubris, the Atlantan society created by comic author Ram V seems controlled and maybe obsessed by their ever present fear of the ocean. This is the portrait of a fragile society, one that despite all the powers and wonders it achieved lives a most perilous life, only waiting for the imminent disaster.

Life in Atlantis is essentially what Geologist Peter Haff termed live in the “technosphere” – an existence that is wholly dependent on technological solutions and utterly lost should these ever fail.

Dipesh Chakrabaty, who quotes Peter Haff in his book “The Climate of History in a Planetary Age” compares Haff’s “technosphere” to a much older text from 1955 by Carl Schmitt. Schmitt there distinguishes between a “terran” and a “maritime” existence, the latter being life onboard of a ship. Chakrabaty concludes: “If Haff’s argument is correct, that the technosphere has become a basic condition for the survival of seven (soon to be nine) billion people today, one could say that we have already made Earth into something like Schmitt’s ship.” (my translations)

Or Ram V’s Atlantis, I would add.

Chakrabaty’s conclusion is even more true for coastal communities. The existence of many of these communities rely on sea walls, dikes, pumps and other technical and architectural structures. It is intriguing to take Ram V’s tale of suppressed fears that become manifest and adapt it to the sensibilities and culture of coastal communities today. One is tempted to ask: How much Atlantis is in cities like New York, Bangkok or Jakarta?

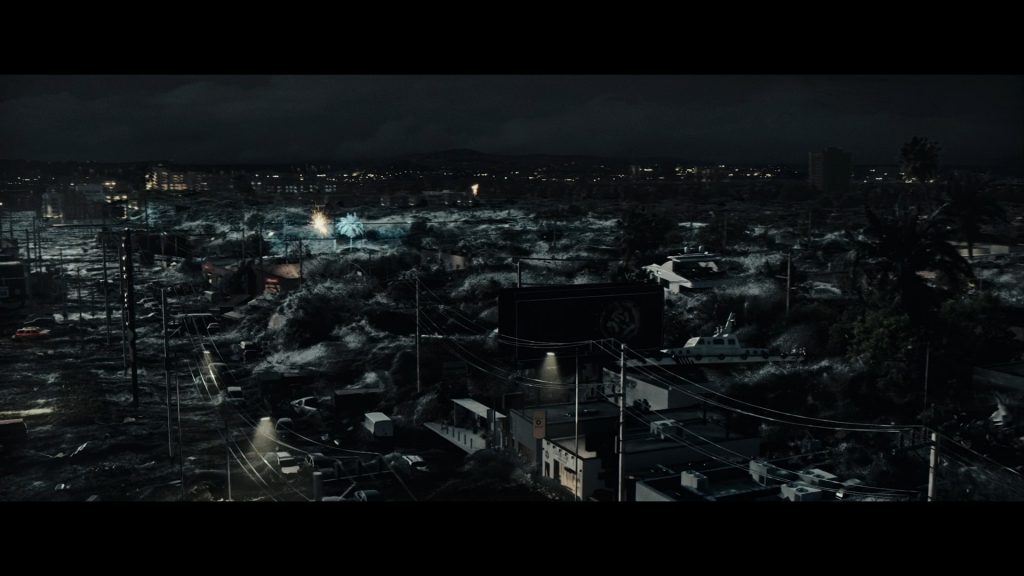

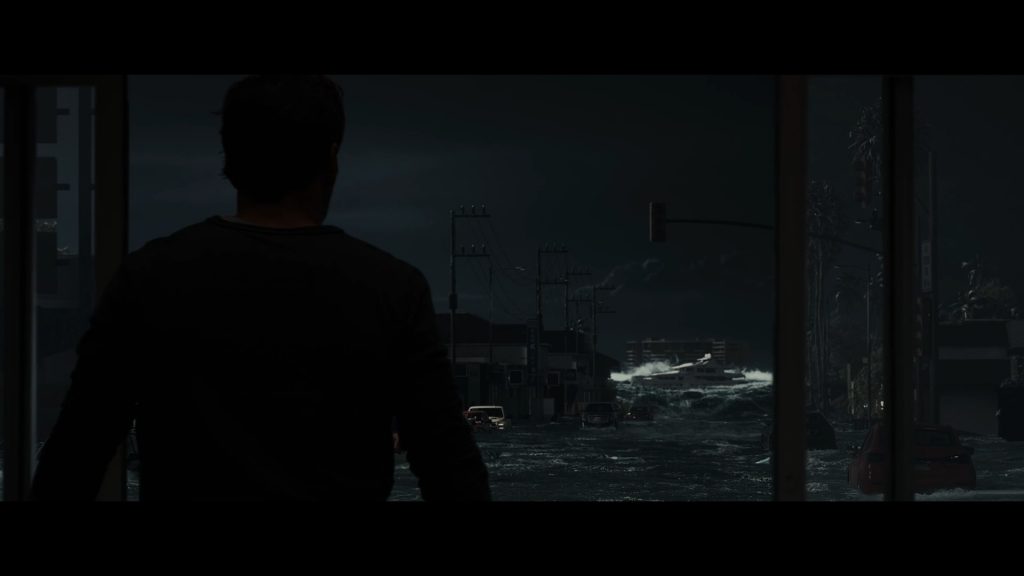

The movie “Moonfall” from 2022 might be the worst movie ever done by Roland Emmerich, the movie director a Canadian journal aptly described as a “disaster-porn artist”. Emmerich has filmed – or rather digitally created – a whole collection of gigantic flood waves over the years from “The Day After Tomorrow” in 2004 to “2012” which was released in 2009. (see my notes here)

“Moonfall” also features a flood scene albeit a visually and atmospherically quite different one. Instead of the usual bird’s eye view shot of one gigantic, towering wave crashing against the city skyline, Emmerich here chooses to depict flooding as a slower, more gradual event. The flood event is taking place at nighttime and the scene has a very dark and shadowy quality. It’s an interesting aesthetic choice that doesn’t fail to create an intense and uncanny effect.

Like in most disaster movies, the perspective is from an elevated and securely removed position. Yet the director here tries to use a less spectacular and slightly more realistic approach to the pheonomenon.

There is however another scene later in the movie that returns to the old formula of the spectacularly crashing giant water wall.

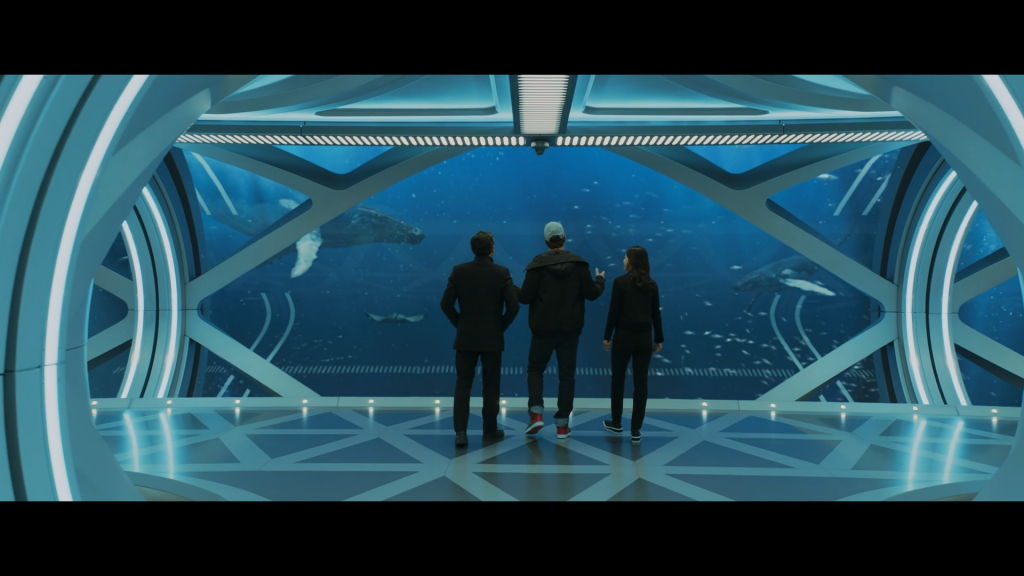

The action movie Meg was released in 2018 and did surprisingly well at the box offices, considering that the shark-vs-man plot seems so outdated and overdone. Apparently it was two decades in the making and it feels a bit like it too watching it. Nevertheless, there is a sequel already in cinemas now testifying to it’s apparent appeal.

The first half of the film is essentially an underwater movie and thus I found it worth analyzing for this blog. The most striking aspect of this underwater scenario seemed to me the interior design of the habitat. As opposed to the usual submarine research base, this submarine station looks a lot more like the rescue bunkers currently advertised for billionaires across the globe or the luxury ocean resorts by South-African hotel mogul Sol Kerzner. Compare this image from the movie and the one from an ad for “Atlantis Hotel” in Sanya Bay, China, below:

This is clearly not coincidental: The second half of the movie plot is prominently set in this very Sanya Bay, currently a prime Chinese tourist destination. The movie is a US-American-Chinese co-production and there are clearly visible marketing intentions at play here. (I have written about the Atlantis hotel group elsewhere in this blog.)

There is also a scene in the movie indicating quite directly the connection between the taste of the mega-rich and this kind of submarine design: Towards the beginning of the movie the US-American Billionaire who finances the research station comes to visit. Entering a freight elevator to go down to the station, he expresses his disdain with the raggedy look of the elevator’s inside, calling it inappropriate for such an expensive research project. He is than relieved to find that the station itself looks much more to his taste.

Here are two more images, with the first one being clearly reminiscent of hotel resorts (with a little girl frolicking along) and the second of the type of sleek office design favored by global market players:

The interior design tells us that this project is actually catering to the taste and needs of the wealthy class more than to science. The topic of submarine refuge is never touched upon verbally in the movie but the images speak quite loudly too, I think. One can’t help notice the stark difference to earlier movies about (and the reality of) submarine research and thus the attractiveness of these fictional rooms.

As billionaires in the real world continue to publicly participate in person in all kinds of enterprises that were once reserved for scientists only, the work environments change accordingly. This of course makes the whole enterprise highly questionable in scientific terms. And I am afraid we are going to see more of this in the future – in film and real life. (See also my post on rich men’s rescue schemes here.)

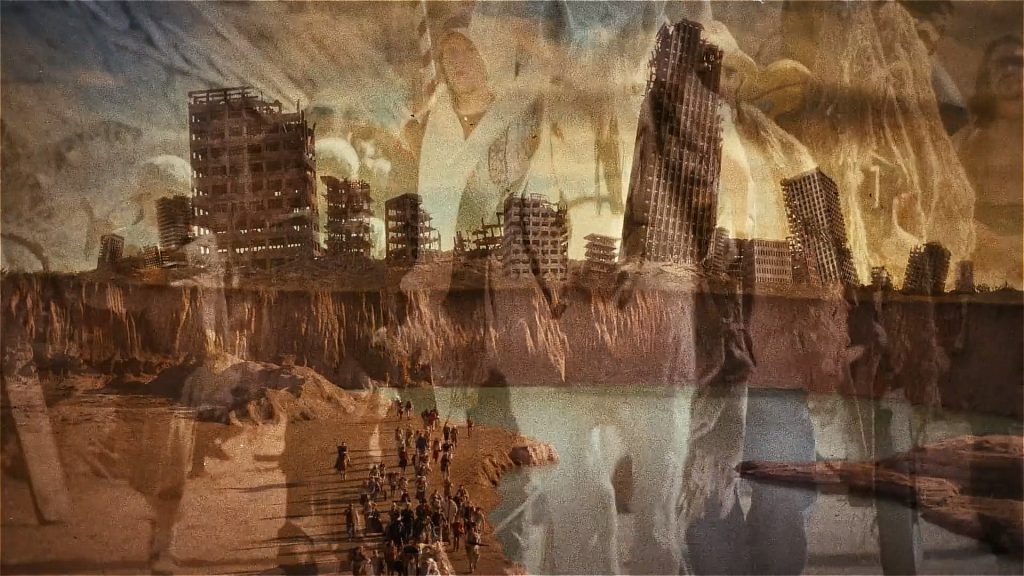

The movie by Robert Rodriguez from 2007 is definitely not a climate narrative. Rather “Planet Terror“, a true retro flick, picks up a theme popular in the 1970s: anihilation through some mysterious chemical experiment gone havoc. Still I found the closing images worth sharing here, as they are not only quite impressive visually, but also because they combine narratives and traditions that are important for coastal climate adaptation.

Set in the US state of Texas the story eventually culminates in a biblical exodus of the last survivors from the barren land called USA to the promised land – called Mexico.

One of the central characters, a Latino in the US himself, gives the crucial advice: “You’ll be able to defend yourselves with the ocean in the back.”

This direction of the exodus is of course a critical comment and reversal of the image of the USA as a promised land for Mexican migrants. But the movie also references the ocean shore in particular as a mythical place of refuge. This might seem like an odd concept, considering that living by the sea actually is living with the proverbial “back against the wall”. But it resonates with the attraction coastal living holds in our culture. This has not always been the case – quite to the contrary. There is historical argument that coastal settlements at least in the Global South are a colonial heritage.

Rodriguez’ garden of Eden combines an ocean idyll with reference to ancient Inka civilisations and a military base, as can be seen in the image above. Obviously these things don’t really match. It’s a very ambivalent and complex collage, very dreamlike and thus inspiring us to think about the relationship between human civilization, destruction and violence and the natural environment as our habitat.

FloodZone is an ongoing photographic series by Anastasia Samoylova, responding to the environmental changes in coastal cities of South Florida. The project began in Miami in 2016, when Samoylova moved to the area and experience living in a tropical environment for the first time.

The works display in an impressive way the ambivalences and the fluid frontiers between city and sea in a community exposed to frequent floodings. I am particularly impressed how artist Samoylova expands the topic and visual themes onto popular imagery and the everyday in the urban scenery.

All images are from the artist’s website.

Thanks to Ulrike Heine for the lead!

In a theme park near Tampa, FL, you can see mermaids perform for you live since 1947.

The producers write on their website: “What do you get when you combine underwater fantasy with SCUBA technology? Why, you get mermaids, gliding and twirling to the soundtrack of children’s fairy tales or popular music. […] In the shows the mermaids (and mermen — called princes) discreetly take mouthfuls of air from the slender breathing tubes while they perform. Even with the air tubes, though, it’s clear that part of being a mermaid is being able to hold your breath for quite a while.”

Interestingly, the audience is seated in a giant glass tank, turning the concept of aquarium inside-out: “The mermaids are swimming in a natural spring; the 500-seat theater is embedded in the side of the spring 16 feet below the surface.”

The park is a business venture by the famous performer and sports swimmer Newt Perry, a former Navy soldier who became a celebrity by appearing in over 100 of filmmaker Grantland Rice‘s “Sportlight” short films over a period of three decades. Newt Perry, once dubbed “The Human Fish”, went on to became a much sought-after film advisor for Hollywood.

Thanks to Bernd Mand for the lead!

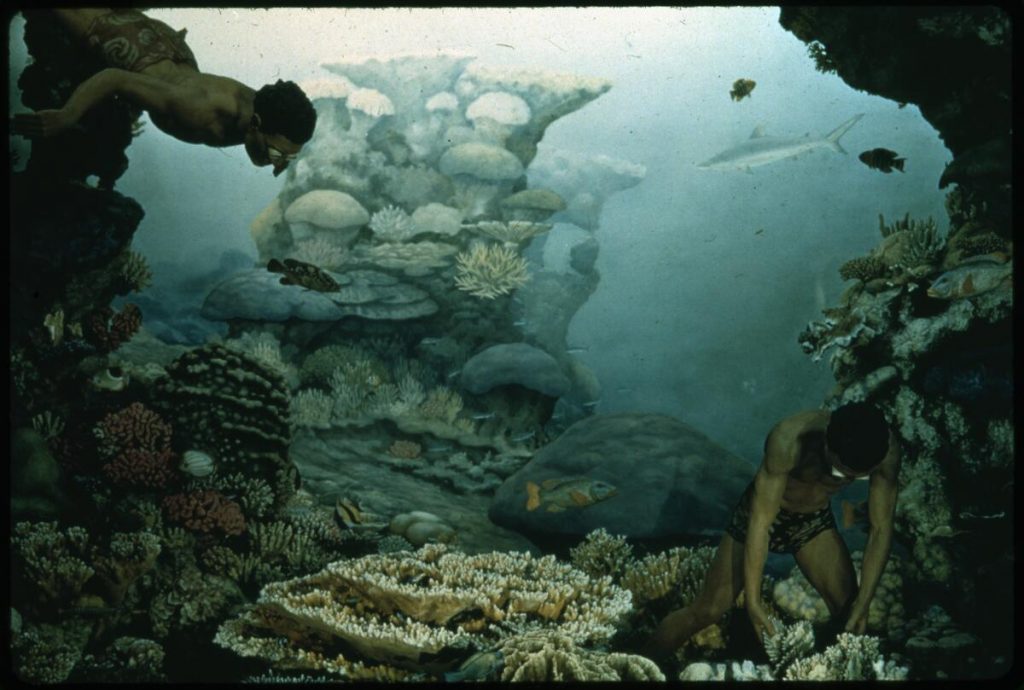

In an essay in which cultural historian Helen M. Rozwadowski traces the intellectual climate surrounding Jacques Cousteaus aquatic utopias, which he managed to manifest temporarily in his Conshelf-experiments (see my post here), she concludes:

“The story of ‘Homo aquaticus’ (a term invented by Cousteau) reveals the extent to which the future of humanity has become tied to the ocean, including as a font of moral rebirth and, more recently, as a refuge for the human species. […] A discourse about the fate of humanity and of the planet”

According to Rozwadowski, aquatic fiction of the 19. and 20. century also reflected racist ideas of white superiority. According to the evolutionist concept that human evolution started in the oceans, popularized by Darwin and Haeckel, diving humans not only came closer to creation, maritime cultures like the Polynesians were portrayed as less developed and closer to human origin. A popular trope of science fiction (and pseudo-science) from the 1950s through 1980s was the “insistence on evolutionary reversal to enable survival”. Man would have to develop backwards, grow gills and move back into the sea if he was to survive the anthropocene.

Rozwadowski paints a picture of a society that views the ocean through the lens of “the twin dynamic of technophobia and technophilia”. Going into and mastering the ocean as a habitat was in the 20. Century at the same time a regressive fantasy and a futurist high-tech adventure. To become aquatic, man either has to regress or needs more and better technology.

As far as moral renewal is concerned, Rozwadowski quotes one of the divers of Cousteaus Conshelf project, Falco, with the words: “I don’t know exactly what happened. I am the same person, yet I am no longer the same. Under the sea everything is . . . moral.” Frederic Dugan, another diver and close associate of Cousteau and co-author of several of his books, “insisted that ‘the coming undersea life will be inspiring,’ drawing parallels to creative historical epochs such as the Renaissance.”

I find this very interesting under the light of current debates around climate crisis and particularly rising sea levels in the anthropocene. Could the threat of flooding also instigate utopian ideas about a moral and evolutionary renewal of mankind in the sea?

Among the stories and books the essay quotes are: Jacques Cousteau with James Dugan: “The Living Sea” (1963), Paul Anderson: “Homo Aquaticus” (Amazing Stories, September 1963), Aleksandr Belayev: “The Amphibian” (1928), Kenneth Bulmer: “City under the Sea” (1957), D.D. Chapman and Deloris Lehman Tarzan: “Red Tide” (1975), and Arthur C. Clarke: “The Challenge of the Sea” (1960) and: “The Ghost of the Grand Banks and the Deep Range” (2001).

Thanks to Lajos Talamonti for the lead.

Lecture by US journalist Jeff Goodell on his book “The Water Will Come” with alot of examples and images around rising sea level and sinking cities. From 2019.

I find this to be one of the really useful and smart talks on the topic, very straight forward and without the usual vanity antics. I have taken the liberty of writing down Goodell’s bullet points that he uses to structure his talk:

Five truths about Sea Level Rise:

1. Storms and hurricanes are like roulette. Sea Level Rise is like gravity.

2. The water will come – the question only is how fast and how high.

3. Trouble begins long before a city becomes the new Atlantis (Opportunities too – I want to add!)

4. Billions of Dollars will be spent on adaptation and protection. A lot of it will not be well spent.

5. Opportunity often comes disguised as catastrophe.

In the end he also gives some very short and helpful advice, what needs to be done: “Remember, this is not an alien invasion.” “Make risk transparent for everyone.” And finally: “Retreat is not a dirty word.”

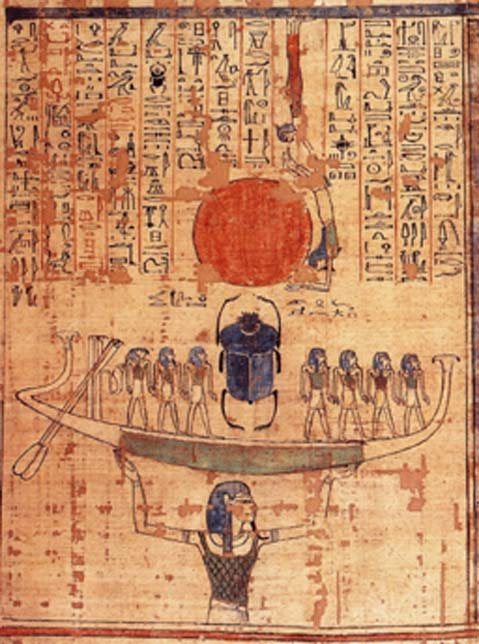

Most ancient cultures share the idea of creation out of water. Be it a cosmic ocean, primordial waters or a more abstract idea of fluid, amorphous chaos. But why is that so? How come that so many creation myths that were formed long before any scientific knowledge about the role of water in biology or physics, agree on the central and fundamental role of water. This article by Morgan Smith gives an overview of the many traces of primordial waters and offers some explanation on the prominent role of water in ancient creation myths.