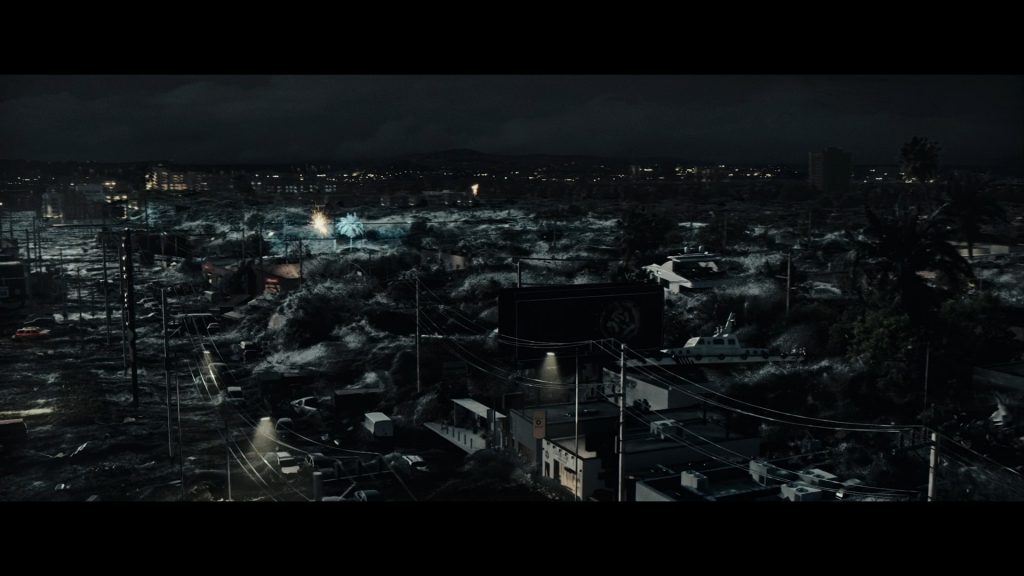

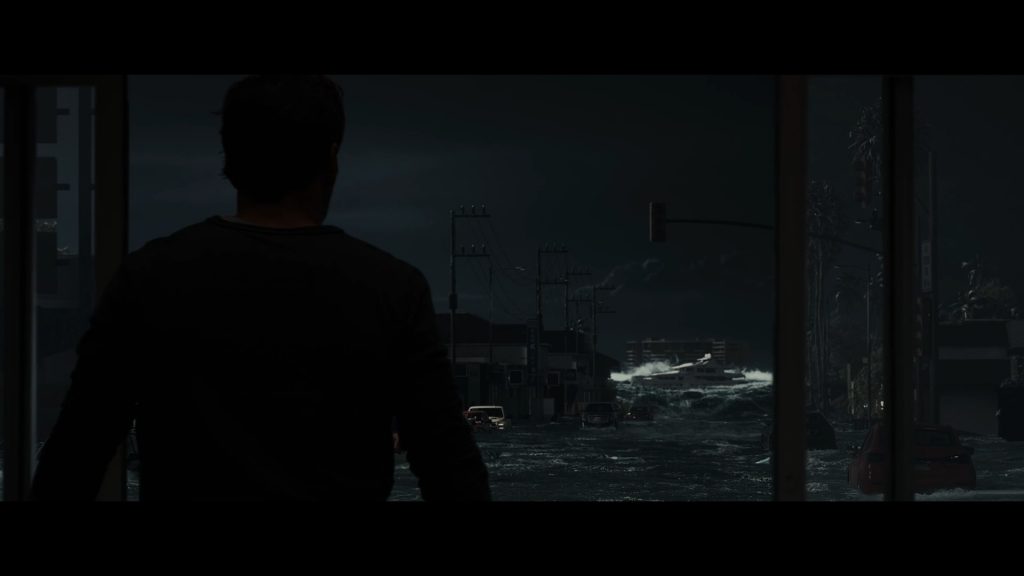

Paraty is a small town and tourist location on Brazil’s Costa Verde, between Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Rising as high as 1,300 meters behind the town are tropical forests and mountains. The village was founded in 1597 and established formally as a town by Portuguese colonists in 1667. The region was populated by the Guaianás Indians. Paraty’s historic center has cobbled streets and buildings dating to its time as a port, during the Brazilian Gold Rush around 1700. Since it is located below-sea-level, the streets flood every full-moon at high tide. Instead of keeping the sea water out, the city planners built a sea wall with special openings to let the water flow in and clean the cobble stone streets.

The following excerpt is from an article by Jose Barbedo et al. Full text can be found here.

“The leading Brazilian urban planner Lucio Costa has described Paraty as the city where the ways of the sea and the paths of the earth meet and interlock. This short description synthesizes the unique landscape that surrounds one of the most valuable colonial settlements in South America.

When the first Portuguese settled in this site in the 16th century, the area was composed of wetlands, which were since progressively drained for the construction of the colonial town. The remnants of the floodplain which were not urbanized have been converted for agricultural use, serving as a buffer zone between the city and the mountains. The two river systems flowing into the urban area (Mateus Nunes and Perequê Açu) have steep gradients, bringing rapid discharges of large volumes of storm water onto the floodplain.

The original settlement was planned to cope with regular high tides and common flooding events; the streets were deliberately designed in a “V” shape, sloping down from the curbs towards the center, in order to keep the houses dry while the streets turned into canals. Today, this fragile balance between the city and its natural environment is threatened by unplanned urban expansion, which in turn may also be aggravated by more frequent extreme rainfall events as registered in recent times.”