The british movie “Captain Nemo and the underwater city” by James Hill picks up the themes and main character Captain Nemo from Jules Verne’s famous novel and the sucessfull 1954 Disney movie on the same material. While the earlier US-movie develops further the theme of the Atomic Age and it’s promises and dangers, the 1969 movie focuses on the idea of alternative, egalitarian communities and the then popular dome structures (gedesic dome) in architecture, the Montreal Biosphere built by Buckminster Fuller in 1967 being maybe the most influential and notable expample.

Each movie thus reflects the topics of it’s time. While the 1954 version is stylistically much closer to a Fin de Siecle, 19. Century aesthetic, the 1969 movie is all 60’s glitz and extravaganza. Furthermore, in the 1969 movie life under water seems like a perfectly sane and technically achievable project, while in 1954 Captain Nemo still clings on to life on land.

This is a fundamental not only technical but also political shift: The idea of leaving the known world behind, going up in space or down into the sea or exiling yourself in an alternative community is now fully developed. The Apollo Program that brought humans into space ran from 1968 to 1972. And in 1963 Jacques Cousteau constructed an underwater station where he stayed with a team of scientists for 30 days. The civilized world had thus become one of several options.

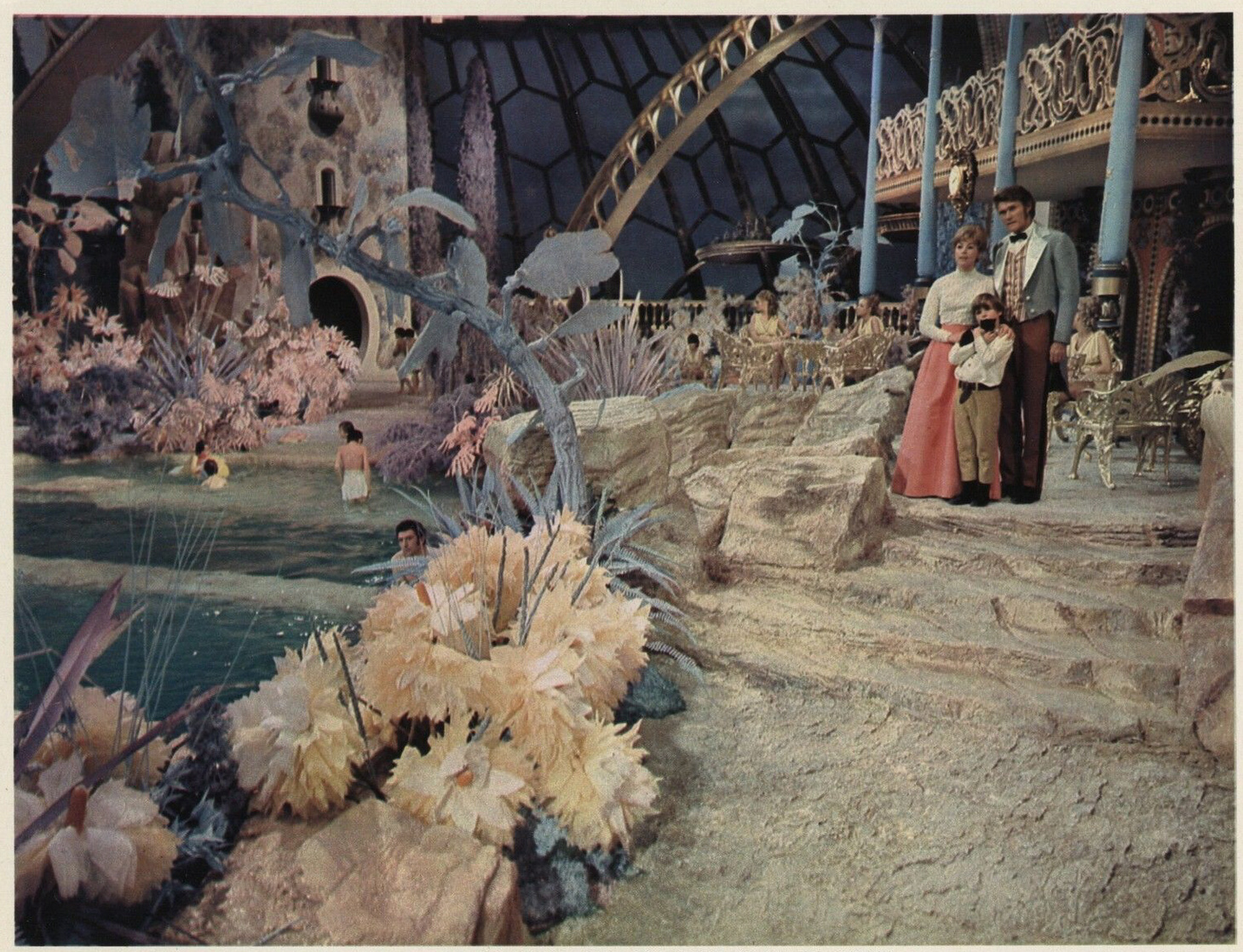

While the screen shot above shows a view of a complete city, it remains the only moment in the movie when the underwater city is actually seen. The action almost exclusively takes place in the rooms of Captain Nemo and in a swimming pool leisure area that looks more like it was directly taken from Blake Edward’s Hollywood satire “The Party” from one year earlier than like anything resembling a city. No houses, no streets, no stores or any other features of an urban environment are depicted.

It seems that the city as a theme and topography of movies did not play a big role in the 1960’s, quite to the opposite of the era of pre-war cinema. (Take for example “Metropolis” from 1927 about another model city run by a benevolent autocrat. See my post here) . The same mixture of artificial wilderness, tropical allure and wild west or pirate movie elements, all covered by a huge dome, can also be found in today’s indoor water parks like Tropical Island near Berlin: